Episode #75: From Childhood Stroke to Triumph

Show Notes: 🎙️ In this captivating episode, join us as we delve into an extraordinary story of resilience, survival, and the unbreakable human spirit. Fred Rutman, the guest of today's show, takes us on a remarkable journey through his experiences of childhood stroke, multiple health battles, and his unwavering determination to overcome them all. 🎧 Tune in as we explore Fred's incredible journey of triumph and discover the resilience that lies within all of us. Don't forget to subscribe, share, and leave a review if you found this episode as inspiring as we did. ******************* Connect with Fred: YouTube: The Dead Man Walking Podcast Instagram: @repeatedlydf Facebook: Repeatedly Dead Fred Author Page LinkedIn: @fredrutman Purchase Fred's book: The Summer I Died Twenty Times: Because Lightning Does Strike the Same Spot Twice https://amzn.to/3L54Mtj ** As an Amazon Associate, I may earn from this purchase. ** Sign up for the Water Prairie Newsletter: https://waterprairie.com/newsletter Support this channel: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/waterprairie Music Used: “LazyDay” by Audionautix is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Artist: http://audionautix.com/

The Water Prairie Chronicles Podcast airs new episodes every Friday at Noon EST!

Find the full directory at waterprairie.com/listen.

Fred Rutman’s Story Beyond a Childhood Stroke

Show Notes:

🎙️ In this captivating episode, join us as we delve into an extraordinary story of resilience, survival, and the unbreakable human spirit. Fred Rutman, the guest of today’s show, takes us on a remarkable journey through his experiences of childhood stroke, multiple health battles, and his unwavering determination to overcome them all.

🎧 Tune in as we explore Fred’s incredible journey of triumph and discover the resilience that lies within all of us. Don’t forget to subscribe, share, and leave a review if you found this episode as inspiring as we did.

*******************

Connect with Fred:

- YouTube: The Dead Man Walking Podcast

- Instagram: @repeatedlydf

- Facebook: Repeatedly Dead Fred Author Page

- LinkedIn: @fredrutman

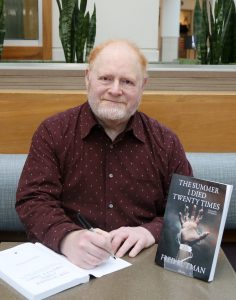

Purchase Fred’s book: The Summer I Died Twenty Times: Because Lightning Does Strike the Same Spot Twice

- https://amzn.to/3L54Mtj

- ** As an Amazon Associate, I may earn from this purchase. **

Sign up for the Water Prairie Newsletter: https://waterprairie.com/newsletter

Support this channel: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/waterprairie

Music Used:

“LazyDay” by Audionautix is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Artist: http://audionautix.com/

Meet Today’s Guest:

Fred was a business prof teaching Finance and Marketing until the summer of 2009 came crashing down on him, with a continuous stream of medical traumas, including his being clinically dead 20 times (There would be more to come). This left him with PTSD, Post-concussion syndrome, and ongoing anxiety. This would have crushed most people. But Fred had another issue. All of this was layered onto his pre-existing medical issues. You see, Fred had a stroke at birth. And it went undiscovered until his mid-30s. That’s not to say he didn’t have an ABI and its accompanying issues. It’s just he didn’t know how to describe his world, and if he could figure that out, who would he tell? The result was being forced onto permanent medical leave.

Fred has since been hospitalized 22 times, undergoing 12 heart procedures. The short story is that his heart was stopping. Each time it stopped, he collapsed, and hit his head, sustaining multiple concussions. They finally figured out he needed a pacemaker. Which was great, until the pacemaker failed in 2013, requiring two emergency surgeries. And it failed again in 2018, with more surgery required. There were additional complications in 2019 and 2020.

In 2018, Fred learned about intermittent fasting. His life hasn’t been the same since. He attributes the large majority of his recovery to the healing powers of IF. Fred spends much of his day talking to people about resiliency, overcoming adversity and living their best, healthy lives.

In summary, Fred shouldn’t even be alive. Nor should he be any level of functional. And yet, here he is trying to be a positive source for anyone who is going through their own trials and tribulations. It’s a power message from an incredibly resilient formerly dead person.

Episode #75: From Childhood Stroke to Triumph

Fred Rutman’s Story Beyond a Childhood Stroke

(Recorded June 28, 2023)

Full Transcript of Interview:

Tonya: Today’s guest is Fred Ruttman, a. k. a. Repeatedly Dead Fred. Fred was a business professor who taught finance and marketing until one summer when his life changed dramatically, including being clinically dead 20 times. But Fred’s amazing story began years before that traumatic summer. And today we’re going to be hearing about how he had a stroke at birth that went undiscovered for years.

And this is a story that you’re not going to want to miss. Fred, welcome to Water Prairie.

Fred: Thank you, Tonya. Happy to be here.

So, I’ve told Fred this ahead of time, but if you’re, if you’re new to listening to the podcast, we’ve been playing a game with our guests this season. And I’m asking each of my guests to provide three facts or pseudo facts about themselves.

And you as a listener, your job is to try to guess which one is true. Which two are true actually, and which one is the lie? And you can post your guess. If you’re watching YouTube, you can post it in the comment section. If you’re not, you can go to Instagram or to Twitter, find the post about this episode and write your guess on there.

And a week after we release that, we’ll post the answer. So, you can always come back and check what your answer is. So, Fred, are you ready to share your facts with us?

You betcha.

All right. What do you have?

Okay. Okay, um, well, I’m Canadian, so it’s the law that I played hockey. I played competitive hockey, college rugby, and I used to be able to bench press 350 pounds.

Number two, I’m Jewish, and I’m a priest.

And number three… I’ve written a book.

All right. All right. Listeners don’t go right now. Finish listening to this episode, but then make sure that you remember to go back and guess afterwards.

So, um, so Fred, your introduction for me was, was interesting enough just with your nickname and everything else.

But I want to get into that in a little, in a little bit, um, starting out. So, you had a stroke when you were young. When was that first discovered?

Uh, in my mid-thirties.

And what was happening in your thirties that they, that they found out about the stroke?

My sister, uh, became friends with a woman whose husband was, um, had a private psyche psychology clinic where he specialized in brain trauma.

And, uh, my sister’s friends said, you know, uh, I think Fred might have a problem. And he should get tested and I got tested and the doctor told me, you have like a severe right hemisphere dysfunction. You know, the right side of your brain is, you know, pretty much obliterated and, uh, and that’s pretty hard to, you know, to wrap your head around.

And, uh, so that’s where it all started, but it started to explain a lot of the things that I found difficult in life and. You know, thankfully they offered some level of, of therapies and treatments that helped me immeasurably. But again, you know, it was the early nineties. So, it doesn’t come close to, you know, the types of therapies and, and, you know, treatments that are available today.

Did they say why it wasn’t recognized when you were a child?

Well, I think just because I’m, you know, 390 years old, uh, they weren’t looking for things like that, uh, as a kid, you know, it just wasn’t that time. It was the early 60s. Um, and, you know, I, I think infant strokes, I’m told are more common than people realize.

Um, but you know, kids are just so neuroplastic that, uh, as they grow their brain, you know, adapts and builds new pathways and things like that without them even knowing. But I think, uh, it’s a, it’s a difficult thing for, for parents. When my parents found out they were devastated, you know, because I had been put in the camp You know, if Fred would stop being such a smart ass and apply himself, you know, he’d do really well.

Um, and, uh, you know, my parents had no, no reason to question that and they had a lot of their own stuff going on. So, it just, uh, I guess I found out when I was supposed to find it.

So, so you said it was your sister who recommended that you go?

My sister’s friend.

Your sister’s friend. So, do you have more than one sibling or was it just the two of you?

Yes, I have a brother.

Okay I’m just trying to think you know How large the family was too because I think that makes it harder to pick up on some things sometimes Especially I’m I I’m like you I was born in the early 60s the and so, you know things were different than they are today and the types of infant checks that were happening weren’t the same as what they have today.

So, so when you’re 30, they’re talking about how your brain is. And I’m thinking, all right, so how, how would I react to that situation? I think I would be like you were, but also at some point it’s got to click to that. Well, I’m still the same person that I was before they told me this. So, it’s, it’s still there.

It’s just that you, you didn’t know that part was there. Um, but did you have like when, uh, other than being a smart aleck, did you have any like challenges in school? Were, were there any like looking back on it? So, nothing’s showing up with that.

Yeah, there was a ton of stuff, but it was all just lumped in the same bucket, you know, Fred’s just not applying himself.

So, you weren’t trying, you weren’t interested.

Yeah, so what I know now that was explained to me probably six or eight years ago with a neurologist Um, I have a condition called hemiparesis. So, the body is split in half vertically, and my left side of my body is slightly paralyzed. All the way up and down, because the right hemisphere is…

So, I’m legally blind in my left eye, but yet for my entire childhood… The doctors just thought I had a lazy eye, so they kept patching me and trying to bring it up, but it wasn’t the eye that was the problem, it was that the brain couldn’t process anything.

Right. So, so they were aware of…

Tons of stuff like that.

Yeah, so they were aware of things that were there, but just didn’t have a name for the cause of it.

They didn’t know it was an issue because, um, in my book, which we’ll talk about in a little bit. Um, I talk about cognitive bias, like the doctors, once they decide on something quite often, they’re not moving off their spot.

So, if they don’t have a reason to, to look for something else, they’re just going to say, you’ve got an unresponsive lazy eye. It’s not common, but it happens. Tough luck.

We’ve, we’ve had similar conversations with some of my other guests that have come on where, um, well, like even, even my own family’s case where you, you run into a doctor who may mean well, but they don’t necessarily look beyond what they think they’re seeing in front of them.

And so, um, so I do, I do hear this a lot. And, and the types of conversations that I’m having with people who have had disabilities or special needs, it, it takes someone to continue asking questions and to keep, to keep researching to, um, to try and find those answers. Um, and I, I think this is a valuable conversation because even today, I think.

It could happen the same as it did with you if it’s not something obvious that’s, that’s jumping out at a doctor. Um, and so not saying that parents, if you have a child with a lazy eye, that that’s not what it is. Maybe that is what it is. But, um, but it, but as we’re always saying on this, you know, you, you want to be asking questions.

You want to be making sure that you’re. that you’re doing some research and that you’re, you’re advocating for your child. Um, so Fred, with, with elementary and also you started school on time, you, you walked before that, you talked when you typically would have been talking and everything.

Oh, did I talk? Yeah.

I’m assuming you’re not the oldest child, or are you?

No, I’m not.

Okay. The, um, the, the oldest isn’t always, always the, the, the talker with an attitude. Is it? No, the oldest is normally the one who’s more nurturing. Of course, I’m, I’m thinking half of our audience is going to call in and say, no, I, I, I actually am, am the old, the older one with an attitude.

But so, I’m thinking that you probably have done a little bit of research now on understanding what. The stroke was, do you feel that you’re, um, equipped to be able to talk about today’s level of what would be happening if a child were to have a stroke?

I think so. I think, you know, parents are looking for markers so much more than they were when I was a kid.

And, you know, the doctors and nurses are also more aware in the birthing room of things that might not be going right or wrong. So, I think there’s a huge advantage. Uh, this will sound funny to having a stroke now versus having a stroke in the 1960s.

So, do you know what some of the signs or red flags might have been?

Um, like if, if a parent today is looking at their child, what it would look like if a child to, to know whether they had had a stroke or not?

Well, I think you, like most medical things, you have to look for trends and groupings. So, if it was only that my lazy, I was lazy. Would be one thing, but if you’re seeing that your kid can’t learn colors because I can’t, I can’t do colors.

So, when you see different things, adding up, that’s when you need to take a deeper dive. I think. Um, even when we were learning to write, I know kids don’t learn to write anymore, so that might not be such a great example, but my handwriting is atrocious. I could not read right between the lines and the teachers were just like screaming at me for, you know, wasting paper and not trying and.

All these other things, um, so I had a comparative test done by this doctor, um, and they do a finger click test. So, they know, you know, they’ve been doing these for dozens and dozens of years, so they know approximately what a normal dominant hand should be able to do. So, I’m currently right dominant hand.

My dominant hand was performing at what a non-dominant hand should perform at. So, there’s, I’m going to guesstimate the number because I don’t remember exactly, but it’s probably a good 30% less. So, say you were supposed to be able to click 100 times. I was only able to click 70. Then they went to my left hand. And, oh my gosh, it was like, even way lower than that. So, it was, uh, pretty obvious.

So, do you think you were probably a left-handed?

It’s possible. My, um, left handedness does run on my mom’s side of the family. And, uh, I can put on a baseball glove and catch with either hand.

Okay. But throwing the ball?

Um, well, throwing the ball, because I’ve got the paralysis, that’s never going to be good. So.

Right. The, uh, yeah. And wasn’t, wasn’t thinking about that, that side of it. Cause I, cause I, I can play golf, um, right handed if I’m driving, but if I’m putting, I put left handed and, um, and I just, I don’t know if it’s visual or if it’s coordination, I’m not sure which one it is, but it’s just always been natural to put left handed and, um, and I can, I can turn it.

The other way around, but I’m not as accurate. with it. It just feels, feels funny. But I hit a baseball right-handed. I’ve never tried it left-handed. I don’t know. Maybe, maybe it would feel more comfortable if I tried it left-handed. But, um, but. I,

I bat right-handed. I golf right-handed. I played hockey left-handed.

So, yeah. So there, um, there, I think, I think there are a lot of, a lot of things like that, that, you know, it’s, it, it can pass over right and left sides. Um, so I’m trying, trying to wrap my head around this. So, you’re right. hemispheres where the damage was done from the stroke, which affects the left side of your body correct?

Yes. For the most part.

Yeah. And, um, tell me more about the paralysis that you’re talking about. So are you able to use your, I mean, you’re, you’re using your left hand while we’re talking here. So, like what, what exactly, like how, how much does that affect you or did it affect you when you were younger even?

Oh, it affected me a lot. Um, you know, it affects your balance. Uh, you know, it affects my depth perception, it affects my visual memory, all, all sorts of things. Um, I, I had, uh, an auditory issue. I could hear the words, I could understand the words, but I couldn’t understand them in a sentence. Uh, I couldn’t track lines while I was reading so I’d reread the same sentence over and over and over again.

So how did you do in school then? Like, did you have tutors that were working with you? What did you do to get through school?

No, I had, you know, my moments of, uh, Stephen Hawking brilliance. And then other days I was just me. So, you know, it turns out I am pretty smart.

Um, I just didn’t know how to learn, and we didn’t know that I needed accommodation. So, you know, after working with this doctor, I’ll, I call them the brain trainers, um, you know, I worked with them for a number of years and I was able to go to university and got a bachelor’s degree and then I went to graduate school and did an MBA, so I did make a lot of progress.

But, you know, it, it’s still nowhere near, uh, normal. So, as a…

So, you did all of that after you were diagnosed?

Yes.

Okay. So, you were in your 30s at the time?

Yes. Um, I don’t know if there’s a paralysis scale. I’ve never talked about this with the neurologist or my other doctors. So, if there was one from, you know, 100% being you’re totally paralyzed, I’d say I’m 25% on my left side.

It’s, it’s that much of a difference between the two sides of my body.

And has that improved since you did the therapy?

No. Not at all.

So, so, so that, because, because I’m wondering too, had, had they known, I mean, you know, it, we, we, we can’t go back to the sixties and, and fix what was happening at that time, but had they known, would getting the therapy right away have helped recover some of the loss that that you had and inabilities like motor skills and everything?

All right, I think most likely Again, because kids are more neuroplastic than we are adults. I mean you really have to grind to achieve neuroplasticity as an adult and You know, I’m still trying to do new things every so often.

I’ll try and draw you know, and so I’ll go on YouTube and You know, how do you draw a face for six-year-olds and, uh, things of that nature, because my dominant hand isn’t really good.

Right. Right. I’m trying to think if I were trying to do it with my left hand, it would, it would take more coordination for drawing to do things.

And if I were, well, I used to write with my left hand all the time, but out of practice now, it would be more awkward with it.

I’d like to think that today the, there are better modalities. for working not only with child stroke victims, but with adult stroke victims, there’s a lot more recovery.

Um, they just know how to, how to treat you better.

Yeah. I think, yeah, time has given more experience, um, more research has been put into brain health even with that. So, I think that’s, that is part of it there. So, parents who have a young child who either had a stroke at birth or before birth even during that process, or they’re, little bit older, but still in those early years. Um, what type of support do you think that they should have involved with them either as parents or just as therapists for their Children? Um, you’re talking about the doctor that you had worked with. Was that a psychologist or a neurologist?

He was a psychologist who had done some specialist specialized training in neurotherapy. Um, I think, you know, today you’d start off with somebody, the doctor getting you hooked up with an occupational therapist and, and a physiotherapist. And, um, you know, depending on the person, like different modalities will work differently for each person.

So even if you and I had the same brain injury, they’re like fingerprints. You know, mine is mine and yours is yours. And the therapy that works for me may not work for you. So, you might have to try a few different modalities to help your child along, but they’re, they’re out there and hopefully, you know, you’re covered by, you know, various insurances and whatever to help you along because it can be pretty expensive.

When you’re in, you’re in Canada and we’re in the U. S. and I know it’s, it’s kind of a battle no matter where you are as far as getting coverage for some of the, the therapies that you have. The, um. So, I, I did want to ask you, so in the intro I talked about, um, you having a traumatic summer. Um, I believe it was the summer of 2009.

Is that correct?

Correct. Yes.

Do you think that the stroke that you had at infancy led to the events that happened that summer?

You know, that’s a great question and I’ve asked my various cardiac experts and they don’t see a correlation. Um, they actually, they know what the condition is that that caused me to have that horrific summer.

Um, and it’s something you don’t usually see until men in their seventies. It hit me in my forties and just hammered me. And, uh, they don’t know why this happened to me. You know, these are things people can make a guesstimate. You know, they can say maybe your vagus nerve was damaged. Or. You know, something like that, but there’s no real way of knowing, but it’s, it’s a good theory.

Yeah. It’s, it’s kind of interesting. You know, wonder cause the brain controls everything. So, um, you know, how was that on there? Well, speaking of that summer, you have a book that’s out that talks about that. Um, in fact, the name of it, I believe is the summer I died 20 times. Is that correct? Do I have the right name?

Yes. So, the summer I died 20 times, tell, tell, tell us about the book. Um, oh, there, I’d say he’s, he is ready for that question. Um, those that are listening, we’ll, we’ll put the link in the show notes so that you can, can access that. Um, but tell, tell us a little bit about it, um, for anyone who may want to, to go and find that.

So, at the time I was a business professor, I was actually teaching an economic session and I was home marking papers. And, um, I suddenly woke up at my desk from what I thought was like a, a deep sleep and it was a horrific experience, and I didn’t know what was happening to me. Um, but the short story is my heart had stopped and, and it had stopped for quite a while.

So, the condition is called, uh, sudden onset severe heart block. So usually at heart block, it goes in stages. And I might have this reversed, so I think third degree is the least problematic, second is, and one is, you know, you’re likely to die. And uh, I, I went from three to one really, really quickly.

And uh, they just, you know, they kept, I’m an overweight, middle aged white guy, so they get heart attack, you’re having a heart attack, you’re having a heart attack, but then they would do the blood work and. The enzymes that show you’re having a heart attack weren’t there. So, but they, they were determined to prove I was having a heart attack.

So, it went on for months until, um, we caught it on film, uh, on a halter man, halter monitor. And, uh, then they saw what was actually happening. And I was in the hospital when that happened and they, um, I forget exactly how many days. Um, I had a good three or four more episodes. Right in the hospital and the best thing about all this It’s almost every time that my heart stopped, and my blood pressure would go to zero.

You have no oxygen in your brain and you’re clinically dead for 30 seconds or more. I would hit my head on whatever was the hardest thing in the immediate area. So, I was just layering it on to that original initial brain damage. It’s just, you know, you know, before we’re, we started recording, you were telling me about, um, the young man working with the toppings.

Yes. I’m just like loading brain damaged toppings.

So, your, so your heart is stopping. Your head is becoming, I’m assuming concussed at that point, if you’re hitting your head really hard. Um, and then you’re already dealing with things that you are trying to, to reverse through therapies and everything to, to, to get everything working in the, in the right direction.

Wow. Well, so this is, this is your story of that journey through that summer, correct?

It starts in that summer. Um, and it’s a tiny bit of a spoiler, so you guys can fast forward if you don’t want to spoil it. So, the fix for my condition is a pacemaker and they finally implanted a pacemaker in me, and the pacemakers are great while they’re working.

Oh, no.

I’m 100% dependent on a pacemaker to replace the electrical signals that aren’t working in my heart anymore. And in 2013, the pacemaker decided to fail.

That wasn’t very long.

No. Um, so we’ve got suspicions of. Of what might have caused that. Um, so, you know, we can go all area 51 on this and stuff like that.

But, um, the doctors again, didn’t understand why I kept clinically dying. Because that’s not something that they would look for. And finally, you know, they figured it out and I had a couple of surgeries that didn’t go very well. And in 2018, it happened again. So, you know, the odds of all of these things collectively happening to me.

Of any of these things happening, it sounds like.

Yeah. It’s just like in the billions and billions.

And you’re still with us to tell us about it, which I appreciate because that has been an, an interesting road. I’d say a rough road too. Um, I’m sure during the, um, cause any, any surgery is tough, but you’ve had more than just surgery going on with all of this. Well, you not only have the book out, but you also have a podcast.

So, tell, tell us about the podcast too, because this is a podcast audience, so they may want to come in and listen to what you’re doing over there.

So going with the summer, I died 20 times theme, and the Repeatedly Dead Fred name, um, I have the dead man walking podcast. So, there’s that dead thing. And I, I have four foundational issues that I talk about in, in the podcast.

So, the first is people who have overcome adversity. And there’s some pretty wild stories out there that, you know, I’m, I’m grateful I get to share and when people hear these, they know they’re not alone, but there is a lot of positive outcomes, despite what you’re going through. I had a lot of people help me get my book published.

So, I like to talk to other emerging authors and people in the publishing business to, you know, hopefully give them a boost. As I mentioned, I was a business professor. So, I love talking small business and financial literacy. And fourthly, the thing that has probably saved my life the most and helped me recover the most is intermittent fasting.

So, you know, I, I talked a lot about health and mental health, intermittent fasting. I probably talked too much about intermittent fasting, my friends would tell me, but, um, it’s truly, uh, the health benefits of intermittent fasting are just off the chart.

It sounds like, um, you’ve got, you’ve got a lot of different things going on with the podcast, but I’m hearing through all of it.

I think a lot of my audience may be interested in that. So um, those are listening or watching on YouTube, go over and check it out. Um, we will put the links to how to find the podcast. Are you on audio and on video?

Uh, I’m not sure I’m on YouTube. I’m also on Spotify and Apple and Amazon that I know of.

Well, this, this is really good. Do you have any other projects working, working on right now?

Well, I’m working on a follow up book, um, because it doesn’t end in 2018, um, there’s a few more heart surgeries. Um, I’ve had a couple of pacemaker surgeries that I think I’m the only person in the world who’s had these. Wow. So, my surgeon is, is a wizard. He’s like Harry Potter level wizard. And, uh, you know, my last surgery, which. Was last November. Um, it was supposed to be 25, 30 minutes and ended up taking three hours.

And, uh, you know, so there’s just, you know, complications that never happened to other people happened to me and, um, you know, my surgeons on the phone with, you know, his surgical mentor and they’re talking and saying, can we do this? Can we do that? Can we, you know, I mean, it was just amazing. And the, uh, there’s a nurse at a monitoring station for the pacemaker.

And she’s calling the pacemaker company to say, you know, what happens if we do this, and we’ll do that. And, you know, it does avoid the warranty, joking about that part, but, you know, I mean, there were a lot of people, uh, working really hard to make that last surgery very successful.

Definitely have a lot, a lot to say and a lot of stories to tell, thankfully, because I’m glad you’re still here among us.

Me too. Um, You know, people ask if, you know, well, I don’t want to get into the religious part, but, you know, somebody wanted you alive is, you know, a version of the, so, you know, what do they want you alive for, you know, you can only make your best guess, but seeing as I’ve been given so many opportunities, I think I have an obligation to try and help other people go through whatever they’re going through.

And that’s what I hope to achieve, you know, with the book and the podcast. And if I get some speaking gigs hint, hint to the audience, love to talk to you in person. Um.

So, he is available if we will have, actually speaking of that, how’s the best way for people to get in touch with you?

Um, they can go to, um, my Instagram, which is @repeatedlydf, I didn’t want to make it too long, so @RepeatedlyDeadFred, um, they can find me there. Or they can find me with my email, Repeatedly.Dead.Fred@gmail. And those are the two easiest. Or LinkedIn, Fred Rutman on LinkedIn.

Well, Fred, thank you for, um, for joining me today. I appreciate you sharing your story.

And, um, listeners, we’re gonna, we’re gonna talk a little bit more about childhood strokes in the coming weeks, but I wanted Fred to come in and tell us about his ’cause this was such an unusual situation and, um, and I, I, I, I don’t like that you’ve had to have all these things happen to you, but I appreciate the story behind them.

That’s not what you said in our initial meeting.

I know, I know my initial response was, “Oh good,” but that’s a whole other story, but, but thank you. Thank you for, for sharing it with, with my audience and letting us get to know you a little bit. And those that are listening, um, be sure to, to check out his book and his podcast as well.

Thank you, Tonya. Much, much appreciated.